Karl Popper, meet the Hydra

Since this website is called Less Wrong, I think there should be a good overview of Karl Popper's falsifiability concept somewhere. It's a surprisingly subtle concept in practice -- the short version is that yes, falsifiability is necessary for a hypothesis to be meaningful, but the hard part is actually pulling off a usable falsification attempt.

There are some posts about falsifiability (e.g. here or here), but they only ever discuss toy examples (rocks falling down, cranks arguing for ancient aliens, invisible dragon in my garage, etc.). There's also this wiki, which introduces the famous history of anomalies in the orbit of Uranus and Mercury, but I think it still doesn't go far enough, because that's the one example that is used everywhere, e.g. Rational Wiki here, and so one might assume it's rather a special case.

I think that toy examples can be useful in debating with crank-leaning people, but if you want to do science better, or learn to use the scientific method outside of the scientific community, this crank-countering approach is unhelpful. Let's instead look at some actual historical science! I tried to cover varying examples in order to see what is a repeating feature and what is incidental.

Karl Popper, meet the Hydra

On endless arguments, the Duhem-Quine thesis, and the necessity of digressions

Our founding question is what drives (scientific) progress. The last two posts were mostly case studies of particular breakthroughs; this will be the first real engagement with theory of how science works, specifically with Karl Popper’s falsifiability. I’ll sum up Popper’s work quite concisely because it’s already well-known, and once again I want to quickly get to a few more subtle case studies.

The demarcation problem

In 1934, the psychologist and soon-to-be philosopher Karl Popper was trying to get out of Austria, sensing the incoming Nazi threat, and he had to write a book to get a permanent position abroad. This book ended up being The Logic of Scientific Discovery, and it ended up popularising the falsifiability theory of science.[1]

Popper’s immediate motivation was the rapid rise in new confusing theories at the beginning of the 20th century, from psychoanalysis (which became popular by the turn of the century) to general relativity (1915; its experimental confirmation in 1919 got it widespread attention). There was also a great clash of political ideologies — Popper had spent his teenage years as a member of an Austrian Marxist party, then left disillusioned and saw the rise of fascism in Europe. All of this must have been a disorienting environment, so he quite naturally wondered about the demarcation problem: how do you separate nonsensical theories from scientific ones?[2]

Popper started from the problem of induction, which we introduced in the last post. His proposed solution is to accept that it is unsolvable, and actual science does not find universally valid statements. Instead of trying to find some fixed system that could produce such statements (like math or a priori truth), he demarked science by the criterion of falsifiability.

The idea is that no theory can be conclusively proven, but theories can be provisionally useful. For a theory to be useful, it must tell us something about the world, and that’s only possible if it makes predictions that could turn out to be wrong.

Theories can thus only be disproven, never conclusively proven, and given a disproof, a theory must be discarded or modified. Science can thus approach truth incrementally, getting less and less wrong as better theories are built out of falsified ones.

In particular, if a theory resists outright attempts to knock it down, that makes it proportionally more reliable. We use the theories that have survived attempts at falsification in the hope that they will keep working for our purposes.

This looks like it could indeed help with the demarcation problem:

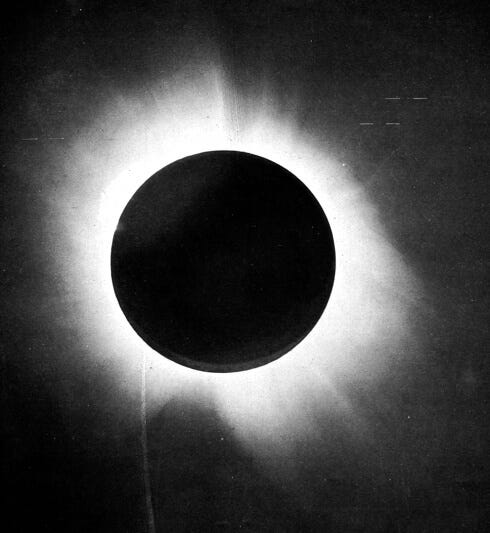

- General relativity made the prediction of starlight bending around the Sun twice more strongly than predicted by Newtonian gravity, which is what got experimentally confirmed in 1919, making Einstein famous.

- Marxism predicted the worldwide communist revolution, sometimes with specific timeframes that turned out to be wrong.[3]

- Psychoanalysis seems applicable to practically any situation whatsoever, and is more of an description of things using a new terminology than a predictive theory — but by this criterion, that is not science.

To quote Popper directly:

I found that those of my friends who were admirers of Marx, Freud, and Adler, were impressed by a number of points common to these theories, and especially by their apparent explanatory power. These theories appeared to be able to explain practically everything that happened within the fields to which they referred. The study of any of them seemed to have the effect of an intellectual conversion or revelation, opening your eyes to a new truth hidden from those not yet initiated. Once your eyes were thus opened you saw confirming instances everywhere: the world was full of verifications of the theory. Whatever happened always confirmed it. Thus its truth appeared manifest; and unbelievers were clearly people who did not want to see the manifest truth; who refused to see it, either because it was against their class interest, or because of their repressions which were still ‘un-analysed’ and crying aloud for treatment.

The most characteristic element in this situation seemed to me the incessant stream of confirmations, of observations which ‘verified’ the theories in question; and this point was constantly emphasized by their adherents. A Marxist could not open a newspaper without finding on every page confirming evidence for his interpretation of history; not only in the news, but also in its presentation — which revealed the class bias of the paper — and especially of course in what the paper did not say. The Freudian analysts emphasized that their theories were constantly verified by their ‘clinical observations’. As for Adler, I was much impressed by a personal experience. Once, in 1919, I reported to him a case which to me did not seem particularly Adlerian, but which he found no difficulty in analysing in terms of his theory of inferiority feelings, although he had not even seen the child. Slightly shocked, I asked him how he could be so sure. ‘Because of my thousandfold experience,’ he replied; whereupon I could not help saying: ‘And with this new case, I suppose, your experience has become thousand-and-one-fold.’

— Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge, page 35

I think I have encountered the falsification theory of science, presented as a solution to the demarcation problem, at some point in school, though I can’t locate it anymore. It is often mentioned by skeptical organisations in fights against various lunatics, such as Rational Wiki here.

The Duhem-Quine thesis

Falsificationism has a clear appeal: it doesn’t need a foundation of absolute truths to stand on, yet gives some mechanism of progress. But there’s a problem, both philosophically and, surprisingly often, in practice. It’s called the Duhem-Quine thesis or confirmation holism.

In the abstract, the fundamental issue is that there are too many possible theories and evidence can never disprove enough of them.[4] Any particular prediction of a theory rests both on the theory itself and on unenumerable auxiliary assumptions — things like instruments being functional and correctly calibrated, samples not being contaminated, data not being corrupted in communication, noise not interfering... (as well as more philosophical assumptions like the scientist being able to trust their own memories). Thus, in principle, a falsification need not falsify the theory — it could just be a stupid bug, or a convoluted phenomenon within the theory. You cannot know for sure when you’ve falsified a theory, because you cannot verify all the assumptions you make.

That also makes the fights with various lunatics so difficult: if you provide contradictory evidence to their theory, they can easily deny your evidence or modify their theory to band-aid that difficulty, and this process can continue ad nauseam without ever reaching an agreement.

There’s a canonical historical example that beautifully illustrates this problem. It concerns Newtonian gravity, which made predictions about the trajectories of planets, and twice looked like it was going to be falsified when the observed orbit of a planet did not match calculations.

Uranus and Neptune

Uranus was generally understood to be a planet somewhere around 1785. In 1821, Alexis Bouvard published astronomical tables predicting its future position. The actual trajectory started to deviate from his tables, and when new tables were made, the discrepancy soon reappeared. In a few years, it was clear that the planet was not following the calculated path.

Under a naïve reading of Popper, this should be a prompt to throw away Newtonian gravity as falsified and look for an alternative theory, but what astronomers of the time actually did was assume that the discrepancy was caused by an additional nearby planet whose gravitational tug was moving Uranus off its predicted path.

This idea existed in 1834, but it took a decade of additional data collection to calculate the necessary position of this eighth planet. Once two astronomers (Urbain le Verrier (at the urgent request of Arago) and John Couch Adams) got the same result in 1846, it took a few months of observations to actually find it.

The planet (now called Neptune) was indeed discovered, rescuing Newtonian gravity — in fact providing a triumph for it, for it allowed astronomers to discover a new planet just by pen-and-paper calculations.

The apparent falsification of Newtonian gravity turned out to be because of the failure of an auxiliary assumption: the finite list of (relevantly big) planets under consideration.

Mercury and Vulcan

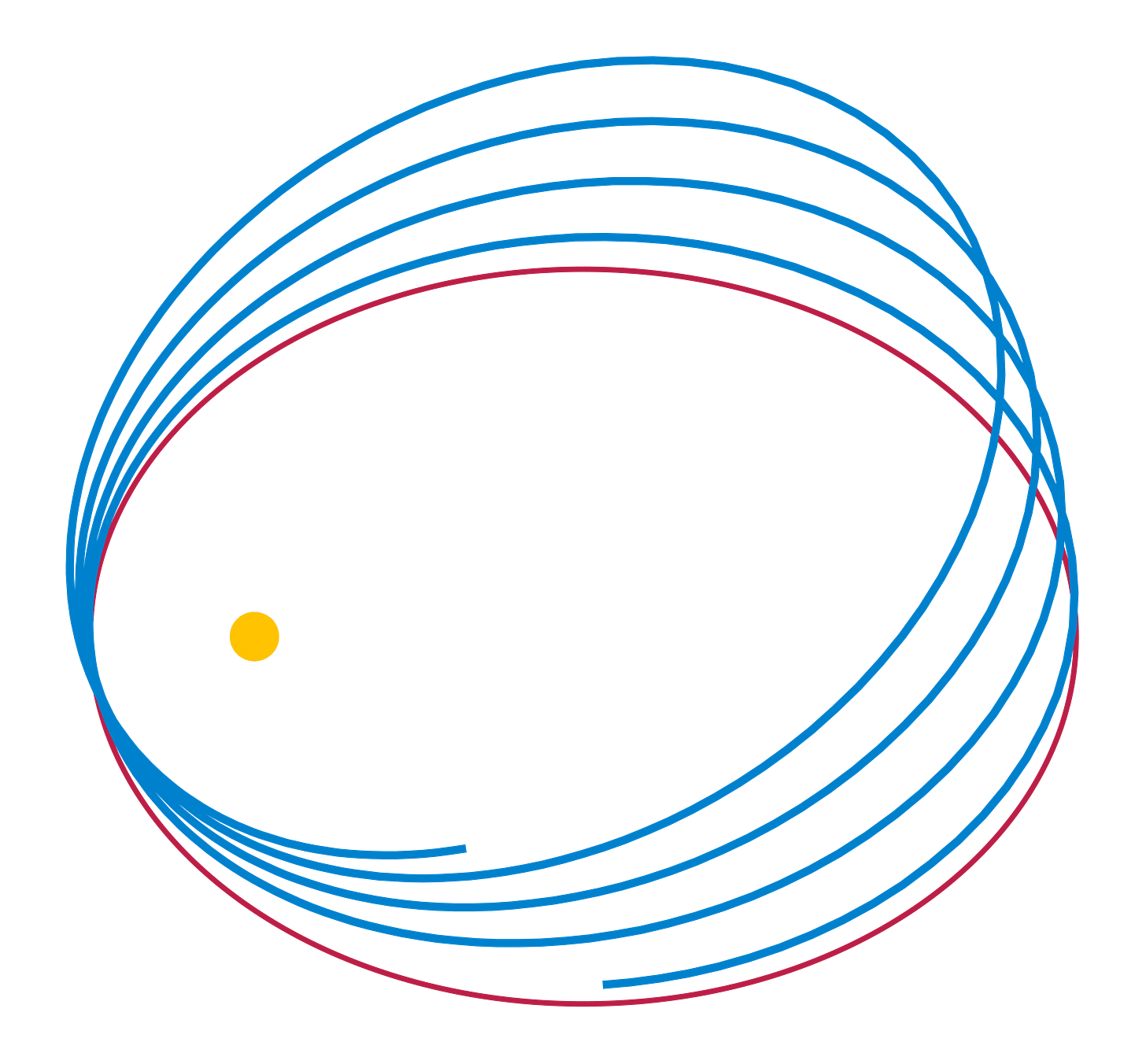

A few years later (in 1859), le Verrier encountered a similar problem with the trajectory of Mercury. Newtonian mechanics for a lone spherical planet orbiting a spherical star predicts an elliptical trajectory, but in practice, the ellipsis precedes around the star because of the tug of other planets (with a tiny contribution from the Sun’s slight oblateness).

For Mercury, this effect can be calculated to be 532 arcseconds per century, but the actual observed effect is 574 arcseconds per century. Again, Newton’s theory looks falsified. But it obviously occurred to le Verrier that it could again be another planet, which started the search for the newly named planet Vulcan. Unlike Neptune, Vulcan would be very close to the Sun, so it would be hard to observe because of the Sun’s glare. The hope was to observe it during a transit or solar eclipse, but those are rare events you have to wait for.

There were many apparent discoveries by amateur astronomers, which usually did not get independently verified. The first reported sighting of a transit of Vulcan came in 1859, then in 1860. In 1878, it was observed during a solar eclipse. Each time, the parameters calculated from that sighting suggested future sightings should be possible, but that replication never came.

This still didn’t disprove Newtonian gravity, because there was also the possibility of the effect coming from an asteroid belt in the same area. There were still searches for Vulcan as late as 1908.

In 1915, Albert Einstein developed his general theory of relativity based on entirely unrelated evidence, and realised that it would create this effect, and he could calculate exactly how strong it would be. When he calculated it to be the exact missing 42 arcseconds per century, he knew the theory was right.[5] This kind of works within Popper’s framework (general relativity was not falsified by this observation while Newtonian gravity was), but the order is backwards (the crucial experiment happened before the correct theory was even known; it is a useful test if it was not the inspiration for general relativity).

The Hydra

All of this is fairly well-described elsewhere (even on Rational Wiki here), including the Neptune/Vulcan example.[6] What I want to stress here is that the D-Q thesis is actually a big problem in practice, and indeed the obstacle that makes science difficult and expensive.[7]

This is where this blog gets its name. If you want to figure one thing out, you would ideally like to do a single crucial experiment, but in fact most scientific tools can only turn one unknown thing into multiple unknown things, like a hydra where you can only answer each question if you first answer several others.

To illustrate, first a less famous example:

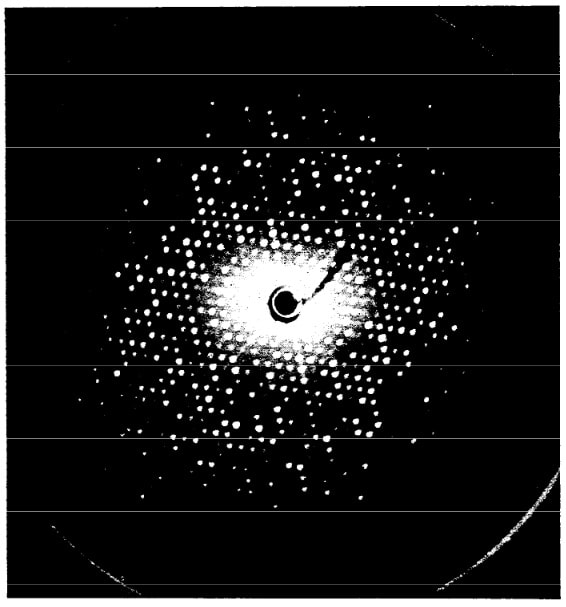

Crystallography and the phase problem

In an undergrad crystallography course, we had to calculate a lot of diffraction patterns. The idea is that you have a crystal with a known structure, shine X-rays at it, and calculate in which directions they get scattered. Throughout the course I was always shaky about why exactly we were doing this — I knew vaguely that X-ray diffraction is used for determining crystal structures, but we never did that, only calculated what we would observe from a known structure.

Now I think the reason we did it this way is that the forward problem of crystal structure → diffraction pattern is a mathematical exercise, while the inverse problem of diffraction pattern → crystal structure is not, because some information is lost in the forward direction.

Mathematically, a simplified first approximation is that there are two functions: the crystal structure is ρ(r) — the electron density depending on position — and the diffraction pattern is I(q), a light intensity map depending on direction (of scattering). The diffraction pattern is (more-or-less) the square of the amplitude of the Fourier transform of the crystal structure:

The problem is that the Fourier transform produces complex numbers, but experimentally we can only see their amplitudes and not their phases.

You can rephrase this problem: by an inverse Fourier transform of I(q), you get ρ(r) convolved with its own mirror image (something called the Patterson function). The hard part of the problem is getting from the Patterson function to the underlying electron density ρ(r). This doesn’t have a single elegant solution, only a bunch of tradeoffs you can take. Since this is often done for finding the structure of biomolecules (especially proteins), I’ll list a few with that application in mind.[8]

- For not-too-complicated crystals, you can try to power through with math alone. The problem is quite constrained simply because the density has to be a real-valued function and cannot be negative. You can hope that it’s in fact constrained enough to have a unique solution, which you can try to find by some iterative algorithm. One thing you can do is repeatedly Fourier-transform back and forth between an electron density and a diffraction pattern, always applying constraints (removing negative numbers in the density half and changing the amplitudes to the observed ones in the intensity half), hoping to converge to a self-consistent answer.

- There is no proof that this procedure works in general,[9] but you can try more specific physical constraints if you initially fail. For more complicated structures like proteins, it’s not computationally possible, and the data isn’t good enough to solve this with more computing power anyway.

- You can do molecular replacement: start the iterative methods from the structure of a similar crystal or a guess of the shape to give the model a better chance of converging, but this introduces a bias to the procedure.

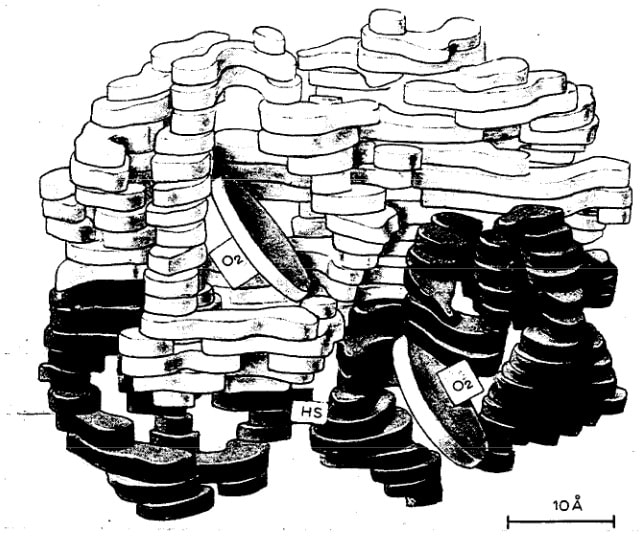

- You can add heavy atoms to your protein; they produce a strong signal that helps localise them in the Patterson function, and then you can use their positions to constrain the rest of the signal. But this only works when the protein keeps its shape after this modification, which it might not (proteins can change shape in one part in response to something happening at a different part of the protein entirely — in fact this is a common protein function, called allostery). This is called multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR); the isomorphous refers to the hope that the structure doesn’t change.

- You can use more sophisticated physics of the interaction of X-rays and matter (part of the reason for the more-or-less above): X-rays can also be absorbed by atoms. This is strongest at specific frequencies for each atom, called absorption edges. At those frequencies, the contribution of the atom to the density function suddenly jumps up.

- In Multi-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (MAD), you measure just below and just above an absorption edge, which is like suddenly getting more density at those atoms only, at which point you can use the same techniques as for MIR, but without the worry that the structure changes.

- Single-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (SAD) is an even more subtle method that works with a single measurement around the absorption edge.

- For both of those, the tradeoff is that you need more sophisticated measuring technology (a synchrotron), and you also need specific atoms in your structure (but they are more biology-friendly ones like selenium or sulfur).

- You might want to just simulate the physics of protein folding using molecular dynamics, but we’re just not there with our computing speed for this to be practical.

- These days, you can use AlphaFold, a machine-learning model that can predict the structure of a protein just from its amino acid sequence (something easily found by chemical means). This is a big deal (it practically solved the “vanilla” problem of protein structure prediction, something nobody had expected to happen for decades to come, and it’s now even used in experimental work for molecular replacement), but it only exists on top of all the previous methods, since it can only be trained on structures where there is a lot of existing experimental data. After proteins, later versions also took on more complicated edge cases and other biomolecules, but the more edgy the cases get, the less reliable AlphaFold gets.

And all of this (including AlphaFold!) only gives you the structure of the protein in a crystal, which is not guaranteed to be the same structure it has in a cell.

As a semi-random example from practice, a while ago I did a class presentation on the discovery / synthesis of a particular ribozyme (a piece of RNA that can catalyse a chemical reaction), and in this paper, the authors found its structure by a mixture of nearly all the approaches and then some:

- First they made several variations of their ribozyme to get one that would even crystallise.

- Then they checked what it did chemically, and from that hypothesised some features it needed to have.

- They they did iterated molecular replacement, which seems to be a rather manual process for building a structure consistent with the diffraction data starting from the structure of a related ribozyme.

- They produced several crystals of the ribozyme with various modifications and used molecular replacement from the original structure to solve their structures.

- Finally, they grew two crystals with added heavy atoms (thallium or selenium) and used SAD on the extra atoms to check for consistency.

- The paper is from 2022, when AlphaFold couldn’t yet work with RNA. I tried pasting the sequence from the paper into Google’s AlphaFold3 server, and got a low-confidence incorrect structure.[10]

As you can see, this is a huge amount of work, a large part of which is trial-and-error and redundant double-checking to wrestle with the hydra.

And each of these steps is its own hydra. From my own experience at a synchrotron measurement, I can say that there’s lots of instrument alignment that must be done before you even get scattering patterns in the first place. I expect that something analogous holds for the chemical procedures.

Now for a story that illustrates just how far the hydra can reach and what it can force you to do before you finally get a precise measurement.

LIGO

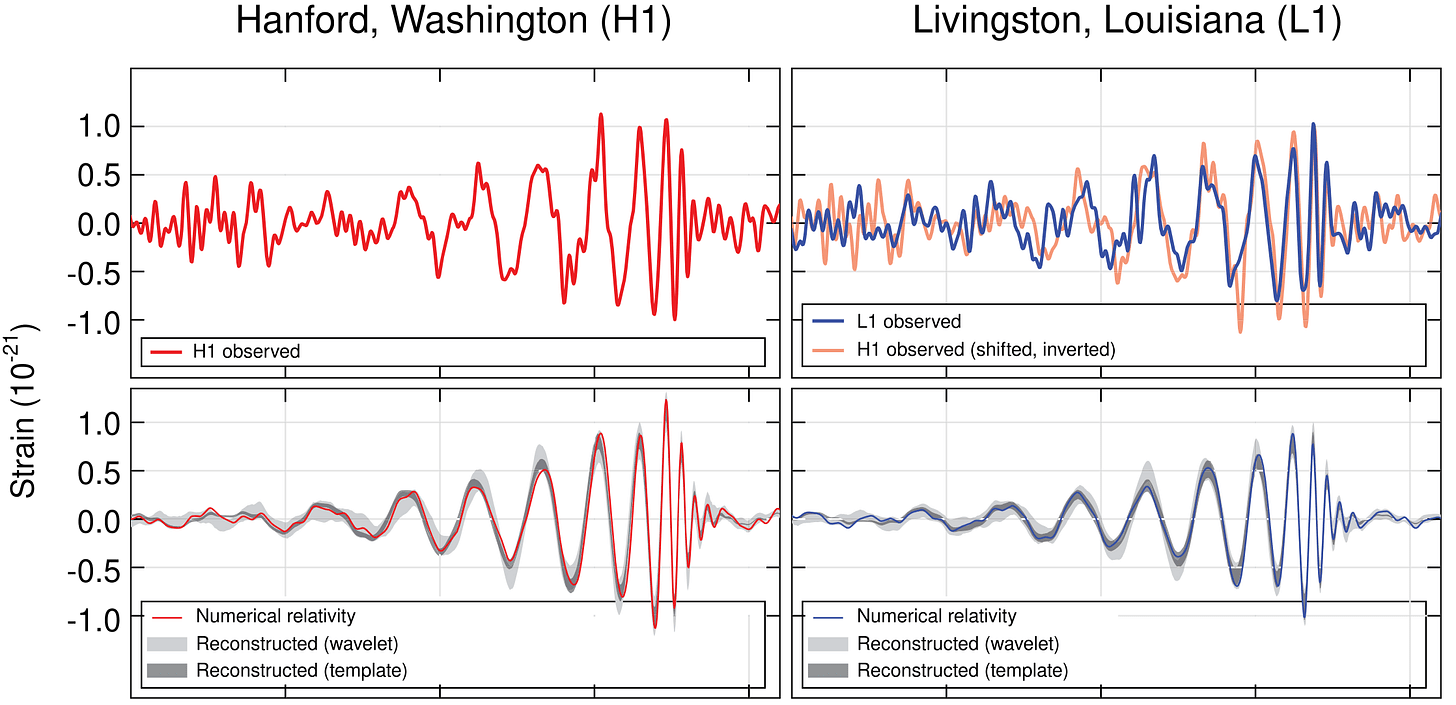

Modern, 21st century experimental physics involves incredibly precise measurements, the pinnacle of which is LIGO, a detector for gravitational waves. Its development needed lots of workarounds for failed auxiliary assumptions.

Detecting gravitational waves requires measuring relative changes in distance between pairs of mirrors down to about 10-22. This obviously requires fancy technology for amplifying such tiny signals — for LIGO, this is done by interferometry.[11] You pass light through two separate 4 km-long paths back and forth hundreds of times (using a Fabry-Pérot cavity), then tune it to destructively interfere, so all of the intensity goes away from a photodetector. If a gravitational wave causes the two paths to become slightly different in length, the destructive interference becomes imperfect and some light makes it to the photodetector. Thus you have two big factors increasing sensitivity: the ratio between the path length and the wavelength of your light, and the ratio between the high laser power (increased by further optics power-recycling tricks) and the sensitivity of the detector.

But that alone would create a detector that measures lots of junk. The difficult and expensive part of designing any such precise experiment is characterising all of the possible things it could be measuring that you don’t want and finding ways to shield them.

Some of those noise sources were known ahead of time and could be prepared for, e.g. by cooling the apparatus down to 0.1 K (to minimise thermal noise) and suspending it on seismic isolation (to avoid having built a mere fancy seismograph),[12] and eventually even using squeezed light to get around quantum noise limits.

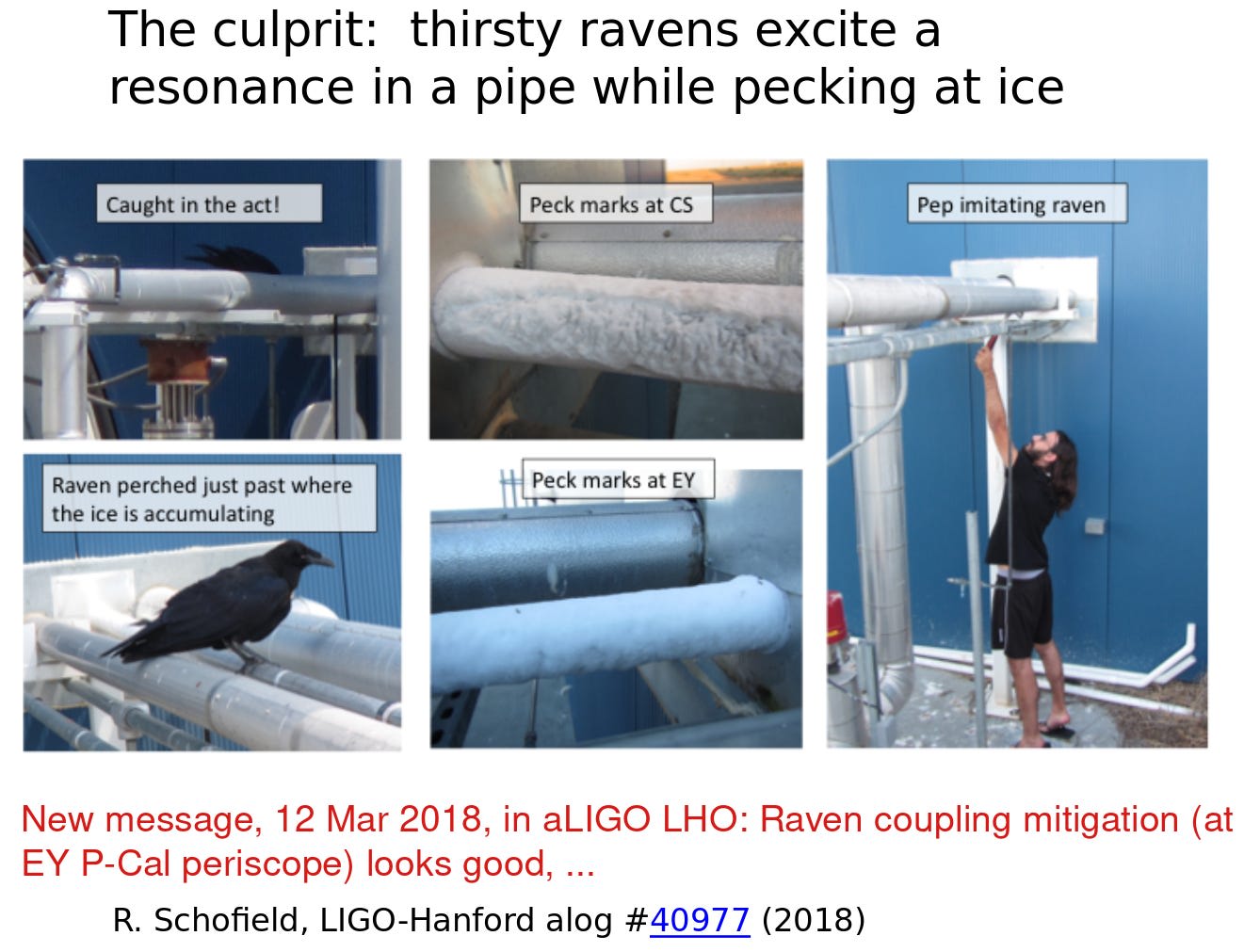

But there are always things you only discover after building the experiment. For example, one summer, spurious signals appeared that turned out to come from something hitting the cooling pipes. That something turned out to be ravens cooling their beaks on the pipes, which were covered in frost. This only got solved when the pipes were shielded so that ravens couldn’t get to them.

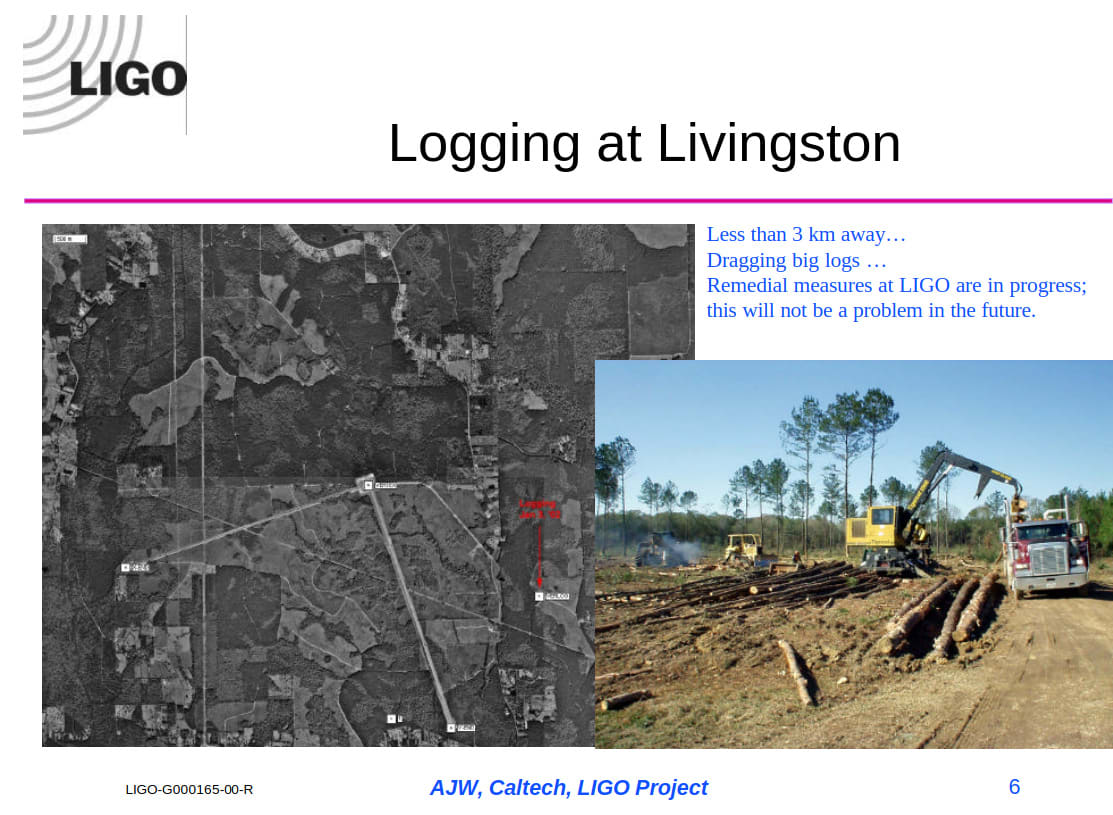

For a tiny window into how much work is involved in all this, check out this presentation from 2002, 13 years before gravitational waves were finally detected. Almost all of it is noise characterisation.[13] Apart from technical sources of noise (such as laser imperfections), there are also things like a logging operation: people drag big logs along the ground 3 kilometres away from the detector, the detector can hear it, and the scientists have to negotiate with the logging people to remove the noise.

In 2015, this work paid off and LIGO detected its first gravitational waves. But how did they know they were indeed detecting gravitational waves, and not some other noise? Two features in particular help make the results trustworthy:

- LIGO consists of two observatories 3000 kilometers apart, one in Louisiana and one in Washington. Local noise sources are generally different at each location, while the waves affect both observatories equally.

- Gravitational waves have a signature shape and behaviour that is already understood and highly constrained. Their propagation at the speed of light exactly matches the delay between the signals at the two locations. The signal speeding up and getting louder towards the end matches its origin from the merger of two black holes. Thus, the signal is so specific that one knows whether it is present or not, which would be hard if you were looking for just “something weird”.

In fact, this data looked so good that the main alternative explanation people worried about for the first few days after seeing it was not temperature, earthquakes, or ravens, but blind testing. There was in fact a system for injecting a fake gravitational wave signal for testing purposes, to see whether LIGO was ready to detect the kind of signal that could be expected. When the actual signal appeared, this testing system was down, but it still took a few days of making absolutely sure that it hadn’t gotten somehow accidentally triggered before it was certain. It helps that the designers weren’t idiots and this system had logs attached, but there is also the possibility of an outside intervention. This goes to say that even the more philosophical doubts about whether you can trust your own memory or your own friends are relevant in practice.

I don’t see any reason to doubt the results based on this, but if you happen to be conspiratorially inclined, you might be interested in a later detection that was reported by LIGO and Virgo (an entirely separate organization), or a slightly later event that was also observed using conventional telescopes all over the world. If you’re so conspiratorially inclined that you’re willing to entertain the entire astronomical community being collectively fooled or deceitful, there’s no way I can help you — but perhaps the section on the demarcation problem below might change your mind.

In the end, the data was so trustworthy that it meant more than just a proof of concept for gravitational wave detection. The black holes that had produced the detected gravitational waves had masses around 30M⊙, which is notably heavier than black holes known before. This discrepancy trickled back through the model of stellar masses used, and the conclusion was that the black holes had to form from stars with a lower metallicity than had previously been assumed.

That shows that not everything anomalous has to be explained away as noise or imperfection: sometimes it is a real effect, and the benefit of having an otherwise trustworthy system is that you can take deviations from your expectations seriously.

The demarcation problem, again

We introduced falsificationism in the context of the demarcation problem and fights with lunatics. Through our case studies we have seen that falsifications, when they even can be produced, are a laborious and uncertain affair even when everybody works in good faith, and impossible against somebody of a sufficiently conspiratorial mind.

When a falsifiable prediction finally works, it always involves some kind of reproducibility: for GR, correctly calculating the orbit of Mercury and the separate 1919 observation of light bending by gravity; for the phase problem, getting similar, chemically sensible structures from multiple crystals by multiple methods; for LIGO, seeing the same results in two (or more) observatories in different places in the world; for scurvy, the curative power of synthesised vitamin C and isolated vitamin C and foods tested by the guinea pig assay.

A lot of crank theories are theoretically falsifiable; the problem is that a falsification doesn’t convince the crank, but only makes them explain it away as a new feature. But this also happens regularly in perfectly legitimate science (e.g. when you throw away a measurement with no signal, because you realise that you forgot to turn your instrument on), so we need a different solution to the demarcation problem.

I propose this: to beat a hydra, you always need some kind of reproducibility between different methods that share as few auxiliary assumptions as possible. If only one lab can reproduce a given experiment, it can be experimental error in their instruments or even fraud. If two labs in different places in the world can reproduce it, it could still be an artifact of the method used.[14] If a different method can reproduce it, the whole thing could still be affected by publication bias, like this:

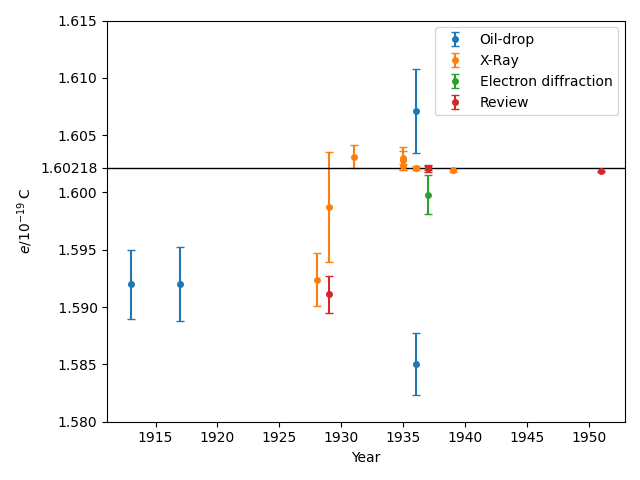

We have learned a lot from experience about how to handle some of the ways we fool ourselves. One example: Millikan measured the charge on an electron by an experiment with falling oil drops, and got an answer which we now know not to be quite right. It’s a little bit off because he had the incorrect value for the viscosity of air. It’s interesting to look at the history of measurements of the charge of an electron, after Millikan. If you plot them as a function of time, you find that one is a little bit bigger than Millikan’s, and the next one’s a little bit bigger than that, and the next one’s a little bit bigger than that, until finally they settle down to a number which is higher.

Why didn’t they discover the new number was higher right away? It’s a thing that scientists are ashamed of--this history--because it’s apparent that people did things like this: When they got a number that was too high above Millikan’s, they thought something must be wrong--and they would look for and find a reason why something might be wrong. When they got a number close to Millikan’s value they didn’t look so hard.[15]

— Richard Feynman, Cargo Cult Science (Caltech 1974 commencement address)

Once a theory is built on by people working in a different field entirely, people who don’t care about the fashions of the original field or its authorities, then it’s nearing certainty. When you develop science, you’re finding things that will still work the same way centuries later, for people from a culture different from your own.

This is what cranks cannot have, because their theories are motivated by some local agenda. They can take up any method and get results they want (and they certainly can set up their own papers, citations, or entire journals), but only at the cost of fighting against the world, of introducing excuses in theory or biasing their experimental data in a preferred direction. But those uninterested in their agenda will be unable to make their results work.

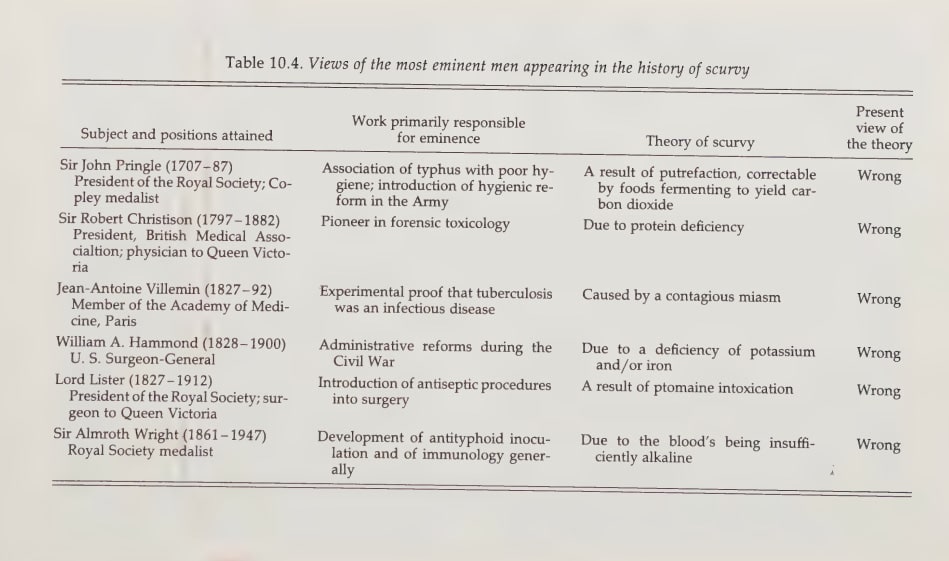

I’ve tried to emphasise that bad science is a spectrum, with complete fraud on one side, somewhat careless mistakes in the middle, and the unavoidable realities of getting funding on the other. Those on the far fraudulent end of that spectrum usually can’t be helped, but that’s a manageable problem in the long run. There’s a lot more potential with the somewhat-biased area on that spectrum. To demonstrate that, I’ll briefly return to the study of scurvy, which was slowed down not by fraud, but by influential experts (in different fields) clinging to their pet theories:

In contrast, those who ended up advancing towards the truth didn’t have a stake in the theories alone, but in outcomes (Blane, Holst and Frølich), or apparently didn’t care at all (Szent-Györgyi[16]). This worked better, because their motivation didn’t push them to anything preconceived.[17]

Nature has a better imagination than any individual human, but humans have a remarkable ability to adapt to its strangeness and make it intuitive, if that’s the path they choose to pursue. I’ll close off with a quote that demonstrates this on a physics field I didn’t want to otherwise breach:

We have not redefined quantum theory; we carry it to its logical conclusion. (...) We learned it second or third hand, as an established discipline whose rules and techniques we came to feel as intuitive and natural, not as a peculiar displacement of classical: we found and find it almost painful to do 19th century physics. The great Bohr-Einstein philosophical debates which fascinate historians and the philosophers are to us a bit wrong-headed (...)

— P. W. Anderson (born 1923, just two years before the big Quantum Year of 1925), More and Different (as quoted in Quantum Mechanics and Electrodynamics by Jaroslav Zamastil and Jakub Benda)

On dei ex machina, again

There’s an interesting distinction in one of the links above (a reaction to AlphaFold) between scientific and engineering problems (emphasis mine):

Engineering problems can be exceedingly difficult, and require the marshaling of inordinate resources, but competent domain experts know the pieces that need to fall into place to solve them. Whether or not a problem can be solved is usually not a question in engineering tasks. It’s a question whether it can be done given the resources available. In scientific problems on the other hand, we don’t know how to go from A to Z. It may turn out that, with a little bit of careful thought (as appears to be the case for AF2), one discovers the solution and it’s easy to go from A to Z, easier than many engineering problems. But prior to that discovery, the path is unknown, and the problem may take a year, a decade, or a century. This is where we were pre-AF2, and why I made a prediction in terms of how fast we will progress that turned out to be wrong. I thought I had a pretty good handle on the problem but I could not estimate it correctly. In some ways it turned out that protein structure prediction is easier than we anticipated. But this is not the point. The point is that before AF2 we didn’t know, and now we do know, that a solution is possible.

— Mohammed AlQuraishi, AlphaFold2 @ CASP14: “It feels like one’s child has left home.”

I also want to insert this quote from another field entirely:

At that time [in 1909], Paris was the center of the aviation world. Aeronautics was neither an industry nor even a science; both were yet to come. It was an art and I might say a passion. Indeed, at that time it was a miracle.

— Aviation pioneer Igor Sikorsky (source)

The point here is that one does not know ahead of time how many detours will be necessary to achieve a given goal, and how much will turn out to be involved.

Not every hydra can be beaten. This can be because there’s some unavoidable technical difficulty right off the bat (as with detecting gravitons), but it can also be because the hydra keeps multiplying with no end in sight, which seems to be the current situation in string theory or fusion power. When one finally gives, it is indeed something of a miracle.

New Hydra heads

A formula has grown in the last three posts: philosophers, case studies, general point. It’s time to end this formula and pursue a new direction. We have been pursuing science and purely scientific case studies for a while, but science exists in a world that also includes other forces and endeavors, and cannot be fully separated from them. The world has occasionally asserted itself, and we have to get back to it eventually. After all, why did Popper come so much closer to the truth than Hume when Hume already had the necessary pieces? I think it’s because Popper was troubled by the problem personally and needed a satisfactory answer.

The essence of the scientific method is to let the world guide you. Some can do that for its own sake, but most have to first be helped by a pragmatism-inducing crisis. So, in a future post, we will treat what happens when you stick to a worldview that is detached from reality for so long that reality asserts itself by force and does the creativity for you: revolutions. (We might also treat Thomas Kuhn and scientific revolutions, if I find anything interesting to say about him despite my antipathies.)

In the long term, I’m headed towards the question of how people do science and how this adaptability is possible. This post was already heading in that direction, but in the future I’d like to write a few things from the actual day-to-day of labwork.

In part (but not entirely!) this is motivated by various attempts to build artificial intelligence, and for that we must first understand machines, and for that we must first understand formal math. This also falls under the original problem of where to get certainty from. (The other part is about natural intelligence and is a lot more broad and unfinished.)

- ^

Popper is not a bad philosopher (he is quite comprehensible and does not make outrageously wrong statements), but this book is wordy for three main reasons:

- He considers numerous philosophical theories of the 1930s that are today simply unheard of.

- He translates his ideas in different formulations over and over in the hope of getting them across.

- There are some warts (connected to the Duhem-Quine thesis) that he never quite overcomes, so there’s a lot of floundering around in the hope of addressing the problem (e.g. a very long treatment of probability, both the mathematics and its interpretations, that never goes anywhere).

I would instead recommend his Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge from 1963, where he actually tells the story of which theories motivated him, and introduces all the interesting concepts within a single chapter.

- ^

I think this also has a second half (inspired by the problems with Marxism): how do you distinguish right from wrong? On the societal level, so many new systems were encountered in that time that this really was non-obvious. Communism proposes fixing a newly recognised evil in society (and it grew out of very real problems of the industrial revolution), fascism proposes reaching a greater height as a species (and scientific progress was visible everywhere in 1934). From the history of 20th century, we also know that this didn’t go well. We’ll return to the ethics perspective in a later post.

- ^

The Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 was driven by people who based their entire plan on a Marxist understanding of history and expected a worldwide communist revolution to follow within months after the Russian Revolution. This led them to bizarrely walk out of WWI peace treaty negotiations, demobilize their army, and declare the war is over — letting their opponents just annex territory unopposed, which nearly sank the entire empire before they managed to course-correct. (I highly recommended to give this link a listen, among other things for the bemused reaction of one German commander.)

- ^

There’s also a related problem: where do theories come from, and how do they have even a chance at correctness, if the space of possibilities is so big? But I’ve already said most of what I have to say about this in the post on scurvy.

- ^

From my GR textbook:

Einstein’s correspondence reveals that it was this particular result which probably brought him the deepest professional satisfaction ever. He experienced heart palpitations and on 17th January 1916 he confirmed to P. Ehrenfest: “I was beside myself with joy and excitement for days.”

- ^

Curiously, Pierre Duhem himself used the example of Uranus to define his thesis in 1904, and yet said in 1906 that Newtonian gravity is likely not a perfect theory and will need modifications, and yet yet, when such a modification (general relativity) actually arrived, he rejected it as “German science”. I find this nationalism utterly bizarre and another example of how people can be trapped by the “spirit of their times”, behaving in ways that are in retrospect seen to be absurd.

- ^

Coincidentally, a few days ago M. was complaining to me about some trouble with his master thesis and wrote: “D-Q is quite a central problem in my life now xD“.

- ^

Source note: I used the textbook An Introduction to Synchrotron Radiation by Philip Willmott, this overview of phase problem solutions, and this manual for a piece of crystallography software.

And yes, I took the opportunity to merge writing this with learning how it works for my own work :)

- ^

Indeed, often it doesn’t. As a toy example, the discrete Patterson function with values 4, 20, 33, 20, 4 corresponds to either 1, 4, 4 or 2, 5, 2.

- ^

I don’t use AlphaFold in my work, so there is some risk that I somehow misused it. I followed that hydra one step and found one RNA crystal structure that I could produce correctly, so hopefully not.

It would make sense for the ribozyme from the paper to be difficult for AlphaFold, because it’s synthetic (found by chemical search among ~1014 random candidates) and thus plausibly far out of the training distribution.

- ^

The same basic principle was also used in the Michelson-Morley experiment; LIGO is a higher-tech version measuring a different effect.

- ^

Michelson had the same problems in his initial 1881 experiment:

The apparatus as above described was constructed by Schmidt and Hænsch of Berlin. It was placed on a stone pier in the Physical Institute, Berlin. The first observation showed, however, that owing to the extreme sensitiveness of the instrument to vibrations, the work could not be carried on during the day. The experiment was next tried at night. When the mirrors were placed half-way on the arms the fringes were visible, but their position could not be measured till after twelve o’clock, and then only at intervals. When the mirrors were moved out to the ends of the arms, the fringes were only occasionally visible.

It thus appeared that the experiments could not be performed in Berlin, and the apparatus was accordingly removed to the Astrophysicalisches Observatorium in Potsdam. Even here the ordinary stone piers did not suffice, and the apparatus was again transferred, this time to a cellar whose circular walls formed the foundation for the pier of the equatorial.

Here, the fringes under ordinary circumstances were sufficiently quiet to measure, but so extraordinarily sensitive was the instrument that the stamping of the pavement, about 100 meters from the observatory, made the fringes disappear entirely!

It took several years to get rid of all this noise, ultimately using this apparatus:

The interferometer itself sits on a block of sandstone on a wooden disk floating on mercury in the basement of a university dormitory. This way, it can be rotated with a single push and no additional vibrations. (image source) - ^

- ^

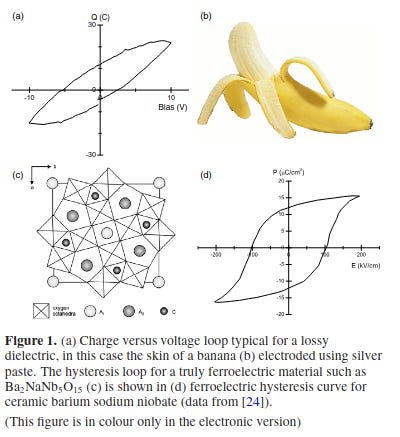

This stuff makes for fun papers. One of them was on the door to my bachelor thesis lab: Ferroelectrics go bananas lists a dozen papers claiming that certain materials are ferroelectric based on a certain measurement, then performs the same measurement on a banana (which is not a ferroelectric) and gets the same result.

Conclusion: If your ‘hysteresis loops‘ look like figure 1(a), please do not publish them. (source) - ^

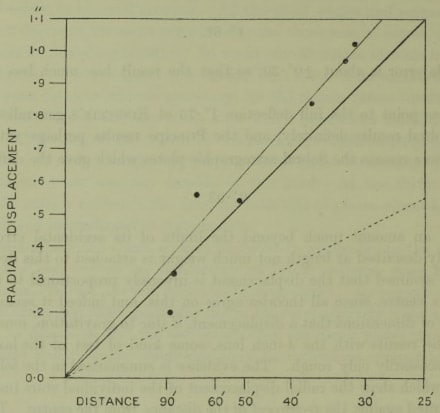

Feynman doesn’t cite the specific studies, though. It seems that this effect did exist, but only for somewhere between one and three studies, and soon a different method gave far more precise results anyway. The plot looks like this:

Make of this what you will. (source) Later in the speech, Feynman also cites a study on rat running experiments with the wrong name of the responsible scientist, which made it hard to track down.

- ^

His comment on the application of his discovery to the cure of scurvy is strange, but probably it was not a harmful attitude (emphasis mine):

One day a nice young American-born Hungarian, J. Swirbely, came to Szeged to work with me. When I asked him what he knew he said he could find out whether a substance contained Vitamin C. I still had a gram or so of my hexuronic acid. I gave it to him to test for vitaminic activity. I told him that I expected he would find it identical with Vitamin C. I always had a strong hunch that this was so but never had tested it. I was not acquainted with animal tests in this field and the whole problem was, for me too glamorous, and vitamins were, to my mind, theoretically uninteresting. “Vitamin” means that one has to eat it. What one has to eat is the first concern of the chef, not the scientist.

— Albert Szent-Györgyi, Lost in the Twentieth Century (1963)

- ^

See also a psychologist’s complaints about how many psychology studies are about trying to find new (and thus publishable) subtle phenomena (like misattribution of arousal), which then often fail to replicate, rather than poking the limits of phenomena that are obviously out there (e.g. people recovering from sad news remarkably quickly or making plans in open-ended situations when the number of possibilities is overwhelming).

Discuss